What We Know… And What We Don’t

The zika virus is plenty scary, and it seems to be getting scarier every day. The CDC has concluded that the bug can cause microcephaly and other birth defects in the fetuses carried by infected mothers. And although infections typically occur via mosquitos, it’s clear that men infected with the virus can spread it to their female partners.

There is some good news. Infection with the zika virus usually causes minor symptoms or none at all. Furthermore, the virus doesn’t seem to hang around long in otherwise healthy adults (a week or two), and once you’ve been infected, it’s likely that you are protected from future infections. Because of this immunity, even the most ferocious outbreaks seem to run out of steam within a few months.

Right now, there’s no vaccine, so anyone that’s not been infected is at some level of risk during an outbreak. We don’t know when in the course of a woman’s zika infection her fetus is at risk. It’s also tough to screen fetuses for microcephaly, at least not until late in the pregnancy.

This all leaves women who are planning to have a baby scratching their heads about what to do.

Experts Disagree About What Women Should Do

There’s a bit of controversy about what women of childbearing age should do if they’re at risk of getting infected with zika.

Some experts recommend that women in the path of the virus (e.g., areas at elevated risk for an outbreak) hold off on getting pregnant. In an interview with the New York Times, for example, Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, said, “It’s a no-brainer… Don’t get pregnant — watch TV for six months and you won’t have a badly hurt baby.”

But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have yet to make a firm recommendation to delay pregnancy. Instead, experts there note that the decision is a very personal one, and that the risks of the zika infection should be discussed between women and their physicians.

Part of the confusion is due to the uncertainty about the facts, but the decision also depends an awful lot on how you feel about various risks to your pregnancy. It rarely gets more personal than that, and as we’re about to see, the CDC’s current position aligns with the evidence far better than a blanket “no-brainer” recommendation.

There’s No Escaping Risk

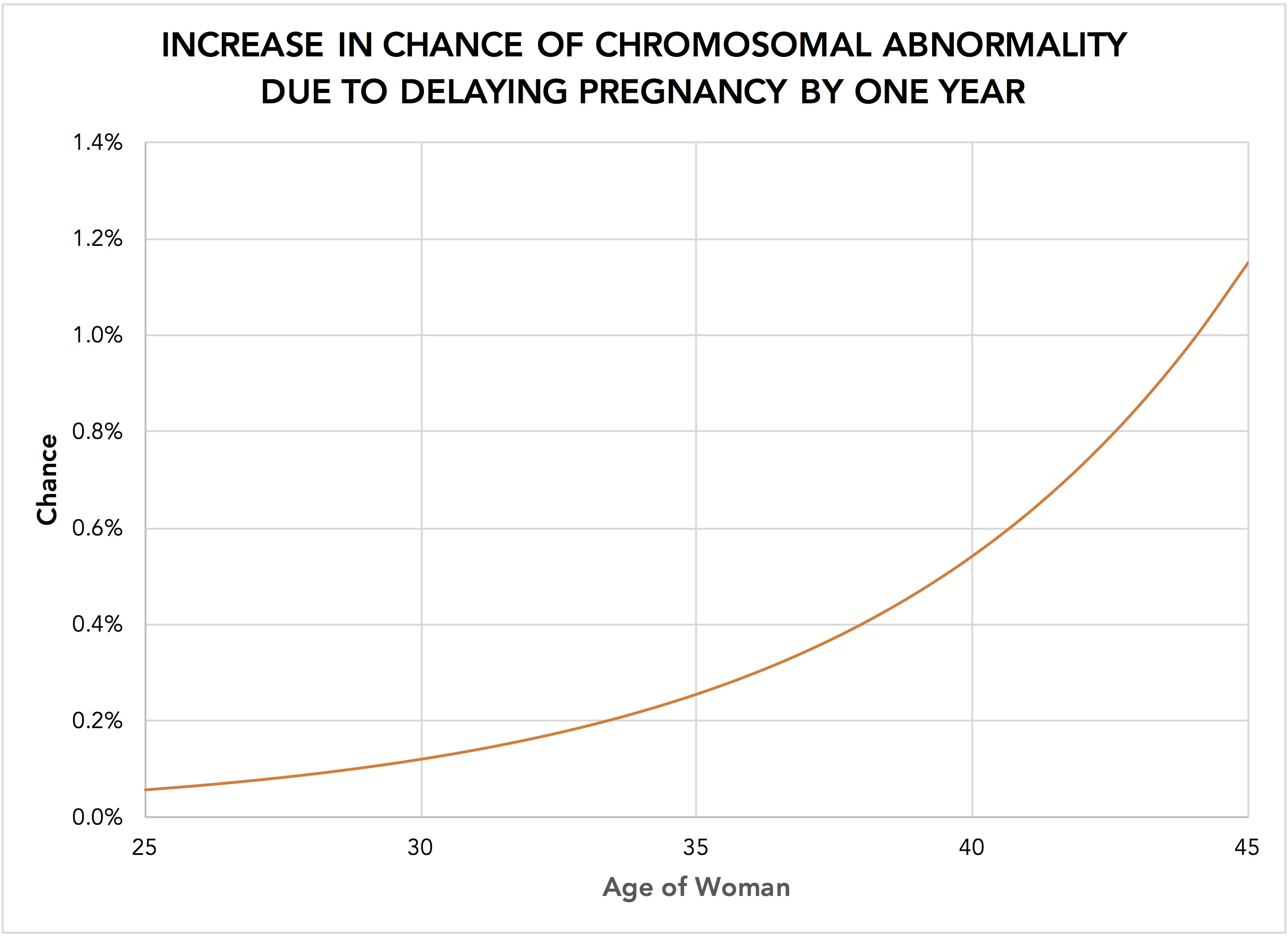

Delaying pregnancy until after a zika outbreak fades will drastically reduce the chance of the birth of a child with microcephaly or other birth defects caused by the virus. But putting off getting pregnant comes with its own downsides, especially for older moms. More specifically, the risk of chromosomal abnormalities rises with maternal age. The change in risk is very small for younger women but it rises rather steeply as women get older. The chart below shows the increase in the chance of any chromosomal abnormality due to delaying pregnancy by one year.

A couple of things to note about this chart. First, it shows the increase in the risk of a chromosomal abnormality associated with a one-year delay in pregnancy for various aged women. Second, the chart displays the risk of an extra or missing chromosome (e.g., trisomy 21, the cause of Down Syndrome) but excludes abnormalities in the structure of chromosomes.

The Risk of Microcephaly

Estimating the chance that a woman seeking to become pregnant will produce a fetus with microcephaly due to zika infection is difficult. We do know, however, that four things must happen:

- The woman must become pregnant

- A zika outbreak must occur during her pregnancy

- The pregnant woman must become infected with the zika virus as a result of the outbreak

- The fetus of the pregnant, infected woman must develop microcephaly

We have pretty good estimates of the chance of delivering a live baby by age (among women seeking to become pregnant), but probabilities of the other three events are sketchy. Researchers have used a statistical model to estimate the chance of fetal microcephaly among infected women; they conclude that chance is about 1%. (That is, for every 100 zika-infected pregnant woman, one will have a fetus with microcephaly.) In a recent (late 2013) outbreak in French Polynesia, 66% of the population became infected.

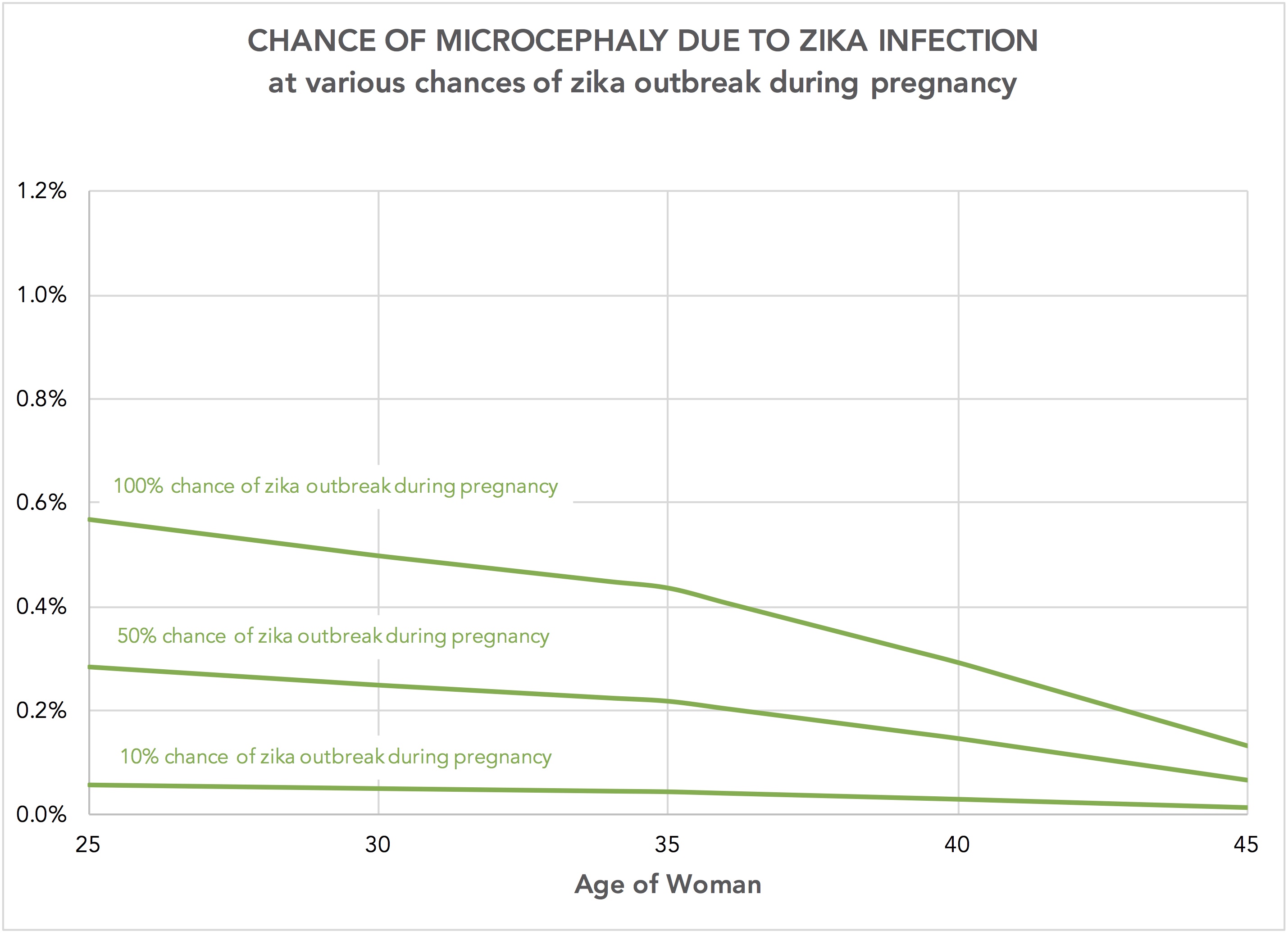

If we assume that the chance that a pregnant woman will become infected during an outbreak to be 66% — equal to the prevalence of infection after that outbreak in French Polynesia — we can estimate the chance of microcephaly among women trying to get pregnant… at least for various guesses of the chance of a zika outbreak during her pregnancy. The following chart shows what that looks like.

There are a couple of things going on in this chart. Obviously, the risk of having a fetus with microcephaly due to zika infection gets smaller as the chance of a zika outbreak during one’s pregnancy gets smaller (i.e., the 100% chance line is above the 50% chance line, and so on). Second, the chance of having a fetus affected by zika-caused microcephaly drops with age; that’s because older women trying to get pregnant are less likely to succeed at that in any year than are their younger counterparts.

A Delicate, Difficult Balance

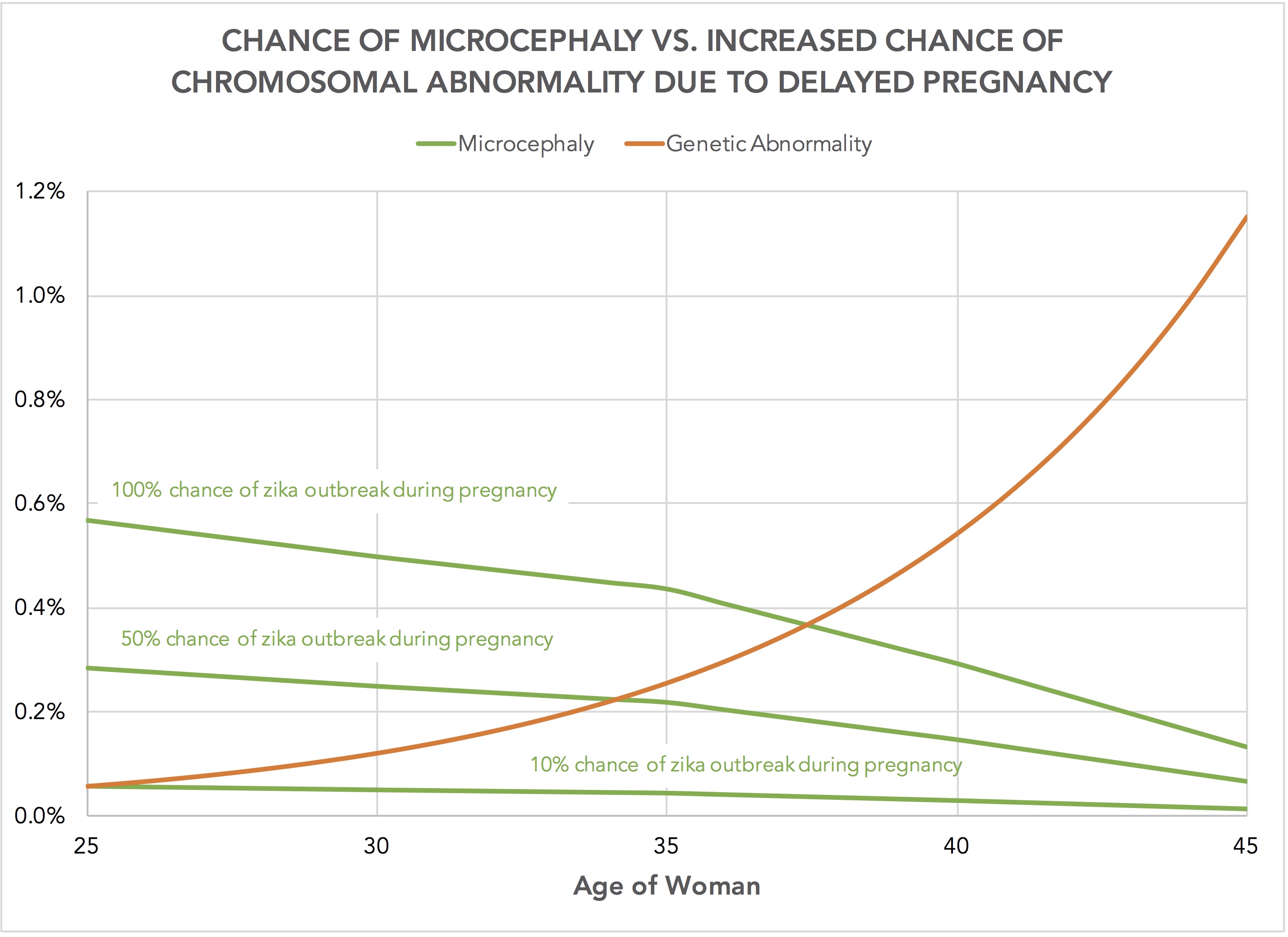

As with any decision, the trick is to understand whether the benefits of an alternative outweigh the costs. In this case, a woman considering becoming pregnant in the face of a potential zika outbreak must weigh the possibility of microcephaly (and other birth defects) caused by a zika infection in the mother against the increased risk – however small – of a chromosomal abnormality that comes from getting pregnant a year later.

We can see how these two competing chances play out by combining the two charts above. The following chart shows how the chance of having a fetus with microcephaly caused by zika compares to the increase in the chance of chromosomal abnormality associated with delaying pregnancy by one year.

No surprise here because this chart simply combines the previous two. But let’s take a moment to recap. With increasing maternal age, the chance of having a fetus with microcephaly due to zika infection declines and the increased chance of having a fetus with a chromosomal abnormality due to delaying the pregnancy rises. In a sense, these risks “compete,” suggesting there may be an age at which delaying the pregnancy does more harm than good.

The Tradeoffs Are Personal

Thankfully, the overwhelming majority of women and babies won’t be affected by this decision; our best estimate is that the chance of microcephaly and the increased chance of chromosomal abnormality are both below 1 in 100 for women of all ages.

The rub, of course, is that as rare as the bad outcomes are, when they happen they are truly devastating. To make a reasonable decision about whether to delay one’s pregnancy in an attempt to avoid birth defects such as microcephaly that could result from zika infection, we need to understand not just the chance of these things happening, but how bad they would be should they happen.

In general, fetuses can be screened for chromosomal abnormalities (e.g., trisomy 21 and 18) early in the pregnancy when a woman can more easily decide how to proceed. In contrast, screening for microcephaly is trickier and generally occurs later in the pregnancy. Some women may feel that a pregnancy in which microcephaly is detected in the third trimester is far worse than one in which, say, trisomy 21 (the abnormality that causes Down Syndrome) is detected in the first trimester. Others may feel that they are equally bad.

If you think these outcomes are equally bad, then that last chart gives you a sense of what you might want to do. If you think the chance of a zika outbreak during your pregnancy is 10%, then delaying your pregnancy is probably not such a good idea, even if you’re young. The increased chance of a chromosomal abnormality from delaying your pregnancy is bigger than the reduction in the chance of having a fetus with microcephaly due to zika. If the chance of a zika outbreak is 50%, then break-even age is about 34; women older than that age do more harm than good by delaying their pregnancies. And if you think it’s a certainty that you’ll be exposed to a zika outbreak during your pregnancy, delaying it makes sense… but only if you’re 37 years of age or younger.

All of that goes out the window, however, if you feel that microcephaly is worse than a chromosomal abnormality. Risk is composed of both a chance of a loss and the magnitude of the loss, and so effectively the green lines in the graph would shift up. As a result, the age break points would shift to the right; delaying the pregnancy would make sense for increasingly older women.

Number Overload

At this point, your head is probably spinning. We’ve taken spotty evidence, made some (reasonable) assumptions, tried to guess how likely a zika outbreak is during a pregnancy, pitted one chance against another, and considered whether one awful outcome is worse or better than another. Many of you are rolling your eyes at trying to take such a complicated problem and break it down into numbers to be run.

In some ways, that’s the point. This is a complicated and uncertain problem, and in the end – even if we could nail down all the estimates – it’s clear that this is a decision that’s likely to be exquisitely sensitive to how women feel about risks, and especially how they feel about microcephaly versus chromosomal birth defects.

And that is precisely why the CDC’s policy to recommend that women talk through this issue with their physicians makes far more sense than a flippant recommendation to “watch TV for six months instead of getting pregnant.”

SOURCES AND ESTIMATES

For a general understanding of zika outbreaks, infection, and risks to the developing fetus, see the CDC’s “tell it like it is” zika information website.

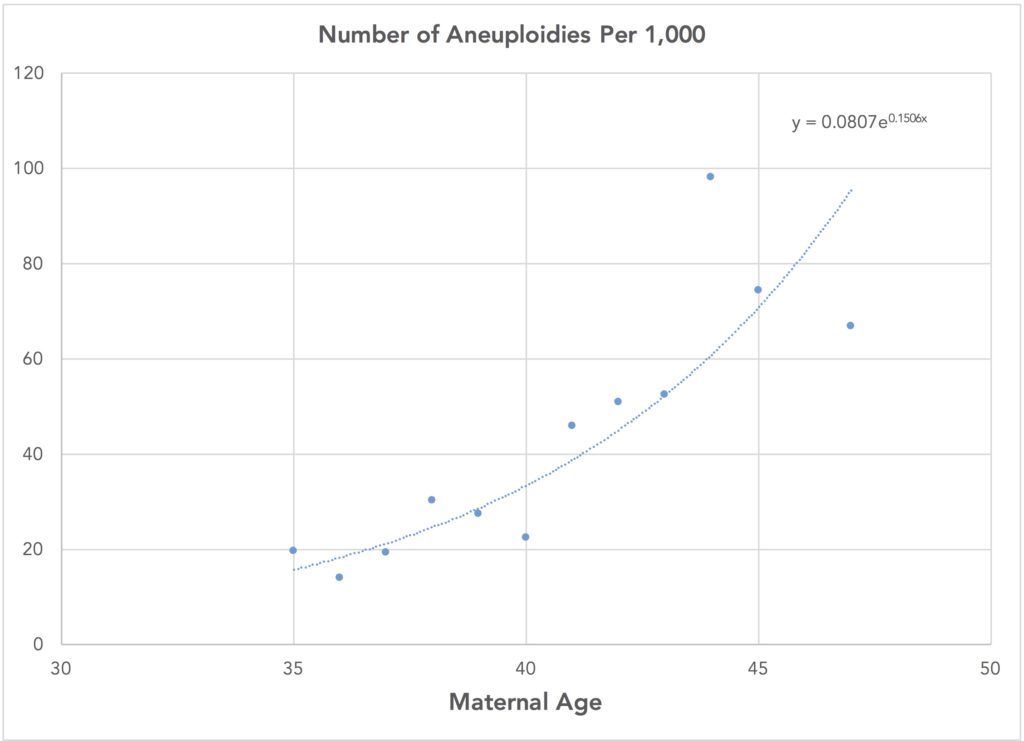

Increase in chance of chromosomal abnormality from delayed pregnancy, by age. To estimate the increase in the chance of chromosomal abnormalities by a year, I fit an exponential curve to data from Kim YJ et al. “Maternal age-specific rates of fetal chromosomal abnormalities in Korean pregnant women of advanced maternal age.” Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2013 May; 56(3): 160–166 (available here). Here’s a chart showing the data and the fitted curve:

I used the fitted curve to then estimate the increase in the chance of a chromosomal abnormality associated with delaying the pregnancy by one year.

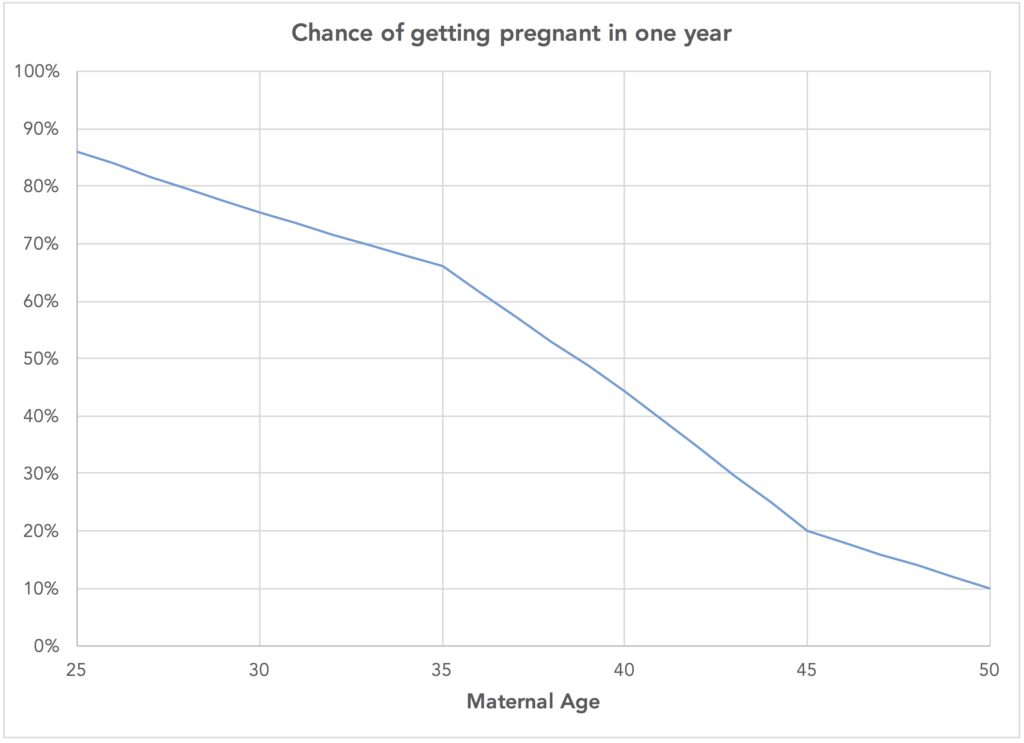

Chance of getting pregnant in one year among women seeking to get pregnant, by age. The chance of pregnancy by age for women trying to get pregnant comes from Leridon, H. (2004). “Can assisted reproduction technology compensate for the natural decline in fertility with age? A model assessment.” Human Reproduction 19 (7): 1548–1553. This study only reports on the chance of birth for women 30, 35, and 40 years of age who are trying to get pregnant (75.4%, 66.0%, and 44.3% respectively). I assumed the chance of getting pregnant within a year of trying was 90% for a 25 year old, 20% for a 45 year old, and 10% for a 50 year old. I then fit a piecewise linear curve to those estimates. Here’s what that looks like:

Chance of a zika outbreak during pregnancy. This chance depends on where the woman lives, how the virus spreads geographically, and the like. I used a wide range of estimates, from 10% to 100%.

Chance woman becomes infected during a zika outbreak. Cauchemez S, Besnard M, Bompard P, et al. (see “Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013-15: a retrospective study.” Lancet 2016 March 15) report that 66% of people in a recent outbreak there eventually became infected with the virus, and that’s the figure I used in this analysis. The chance for any woman, of course, may depend on what protective measures are taken and how effective those measures might be.

Chance of microcephaly in fetuses of zika-infected women. As noted, we don’t know with certainty the chance of a fetus developing microcephaly if the woman is infected with zika. Researchers recently estimated the chance to be 1% (see Cauchemez S, Besnard M, Bompard P, et al. “Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013-15: a retrospective study.” Lancet 2016 March 15), and that’s what I used in this analysis. Two important caveats. First, there is still a lot of uncertainty about this chance, and the 1% estimate that I used could turn out to be low. Second, little is known about how this risk to the fetus varies depending on the developmental stage of the fetus at the time the woman becomes infected with the virus. To the degree than the estimate of the chance of an outbreak during a woman’s pregnancy is interpreted to mean the full nine months of gestation, the 1% estimate could be high.