It’s been a while since the Covid-19 epidemic has turned our world upside down. As a result, there’s a ton of interest in getting us all back to work as soon as possible. And that’s totally understandable: a frozen economy isn’t good for anyone.

One interesting proposal is the use of “immunity passports.” These passports would certify that the bearer is immune to infection with the Covid-19 (C19) virus. The idea is to identify people who have been infected (even if they don’t know it), recovered, and who have developed immunity to the virus. Identifying these folks is kind of a big deal because they could be key to helping to restart the economy.

Figuring Out Who’s Immune

How do we know if someone is immune? Well, one way is to keep track of people who have tested positive for the virus itself and subsequently recovered. That’s a bit problematic, though, for a couple of reasons.

First, people who’ve gotten sick enough with the C19 virus to receive testing may not be well suited to restarting the economy. Many of these folks are older and have other health issues. They and their families have also been through the wringer.

Second, to have gotten tested for the virus (at least in the US), people have to have shown several symptoms of C19. Because not everyone who has been infected with the virus has symptoms, there may be a pool of people with immunity that never got tested for the virus.

And that’s precisely the idea behind antibody testing. Instead of testing for the virus itself, these tests look to see whether the body has successfully mounted a response to C19 infection. If we can find these people, and if we can safely assume that having antibodies means someone is immune to reinfection (not known for sure, but this is what most virologists and infectious disease experts believe), then they can move freely about without risk to themselves or to others.

Imperfect Antibody Tests Pose a Serious Problem

For immunity passports to work, a lot of obstacles need to be overcome including producing enough antibody tests, fielding them effectively, developing a solid process for certifying individual results, etc.

A more fundamental challenge for immunity passports is the performance of the antibody tests themselves. All tests have some degree of error. These errors are of two types: false negatives and false positives.

In the case of antibody tests, a false negative happens when a test says someone doesn’t have antibodies to the C19 virus when they actually do. A false positive happens when a test says someone does have C19 antibodies when they actually don’t.

The Key Challenge: False Positives

For immunity passports, the greater problem is the rate of false positives. That’s because these errors would lead people to be labeled as immune to the C19 virus when they’re actually not.

Antibody tests are being developed quickly, so it’s not totally clear what the false positive rates will be. Cellex is the first company to gain FDA approval for a C19 antibody test, and they reported a false positive rate of about 4%.

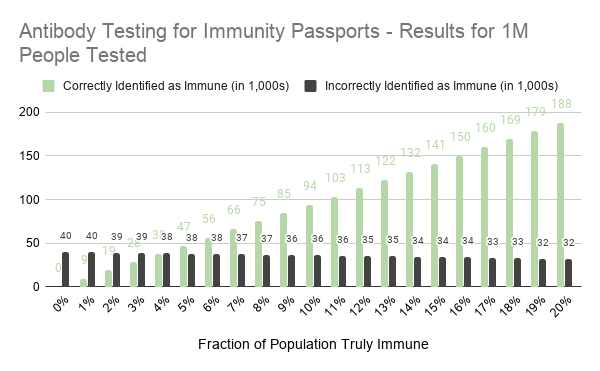

Although this seems like a low error rate, let’s consider what would happen were the test to be deployed in a population of 1 million people. We will assume that the true rate of C19 immunity ranges from 0% to 20%. The number of false positives is 4% times the number of people who don’t have immunity. With a group of 1M people and a range of true immunity between 0% – 20%, the number of people without immunity is somewhere between 800,000 and 1,000,000. If you multiply those numbers by 4%, you’ll find that between 32,000 and 40,000 people will be falsely identified as having immunity.

In short, with a false positive rate of 4% and for every 1M people tested about 30,000 to 40,000 people will be granted “immunity passports” but will not be immune to the C19 virus. In other words, the false positive rate needs to be quite low before antibody tests can be used to grant people immunity passports.

The chart below shows how the results of antibody testing vary with different underlying rates of true immunity. It assumes an antibody test with a false positive rate of 4%, and false negative rate of 6%, consistent with the rates reported to the FDA by Cellex.

What Happens Next?

So, what’s next? First, developers of the antibody tests need to focus on minimizing the false positive rate. This is tricky because the two types of testing errors tend to move in opposite directions: lowering the false positive rate will likely increase the false negative rate. The higher the false negative rate, the fewer truly immune people the test will identify, defeating the purpose of the program.

Second, public health folks will certainly be working to expand viral testing outside of clinical settings (e.g., hospitals). They’ll probably do this along two parallel paths.

The first path will be to identify current pools of infection, isolating and monitoring those who are infected, tracing those who’ve had contact with those who are infected and quarantining them. This is the bread and butter legwork of applied epidemiology. Given the shortage of viral tests and public health staff, a lot of innovative thinking will go into how to get this done most efficiently.

In lockstep, communities will focus on viral testing to do surveillance. The goal will be to better understand – on an almost daily basis – how well the virus is contained. Once these surveillance programs are put into place, state and local leaders will begin to ease up on the various programs (e.g., social distancing, stay-at-home notices) while carefully watching the prevalence of C19 infection via these surveillance systems. If and when the infection rate climbs, the programs will need to be reimplemented.

This is the new normal, and it’s likely to remain that way until we achieve either breakthrough treatments for C19 or an effective vaccine.