The tricky balance between saving lives and protecting the economy

Faced with the possibility of their healthcare systems being overwhelmed with Covid-19 patients, most developed countries implemented some form of “locking down.” Citizens were told to stay home except in the case of emergencies or to buy food or medicine. Restaurants and bars were closed. The use of face masks was sometimes deemed mandatory. Schools had to learn how to operate online.

Sweden took a completely different approach. Middle and elementary schools remained open, as did restaurants, bars, beauty salons, and gyms. Although citizens were asked to socially distance, doing so wasn’t mandated.

Why did Sweden go this direction in light of a dangerous pandemic? Some argue that their goal is to get to herd immunity as quickly as possible; authorities deny that is the case. One thing is sure: Sweden’s approach makes it far easier to illuminate a fundamental dilemma — the inherent tension between public health and economic activity inherent when making policy decisions about how to manage an epidemic.

How is Sweden Doing?

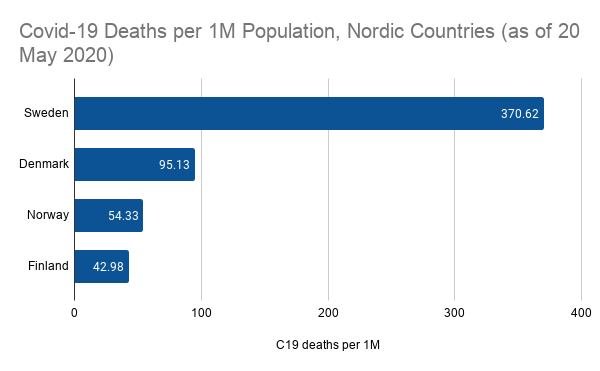

The best way to gauge whether Sweden’s approach is causing excess deaths due to Covid-19 is to compare its outcomes to those of its closest Nordic neighbors: Denmark, Norway, and Finland. This helps to control for differences that exist in comparisons with other countries.

The following chart shows the number of Covid-19 (or C19) deaths per 1 million population for Sweden and three other Nordic countries as of 20 May 2020. Note that Sweden’s C19 death rate is far greater than its neighbors.

All other things being equal, it’s pretty clear that Sweden’s more relaxed approach to managing the spread of the virus is leading to additional C19 deaths.

How many excess deaths? If we compare Sweden’s C19 deaths per 1M to the average of its neighbors, we can get an idea. As of 20 May 2020, Denmark, Norway, and Finland together averaged 64.1 deaths per 1M. That means that the excess deaths per 1M inhabitants associated with Sweden’s more lax approach is 306.5 (370.6 deaths per 1M minus 64.1 deaths per 1M). Sweden has a population of roughly 10M people, so this implies that about 3,700 additional deaths (10M x 307 deaths per million) are associated with the Swedish C19 policy.

In short, as of this date, it’s reasonable to estimate that the Swedish approach has added an additional 3,700 deaths to its C19 mortality count.

But What About Sweden’s Economy?

It’s too early to tell how much damage to the Swedish economy has been prevented by avoiding the stricter lockdown policies pursued by other countries. But we can get a hint at what the experts think.

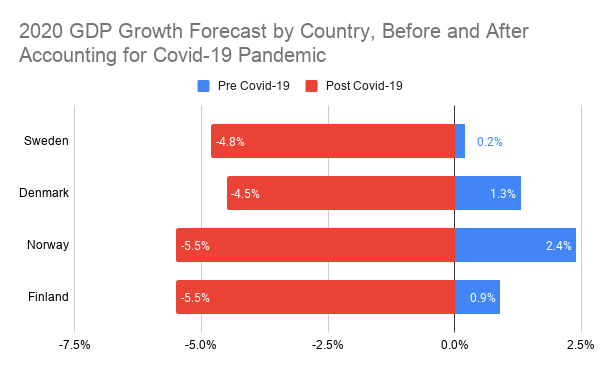

To do this, I examined the 2020 GDP growth forecasts for Sweden, Denmark, Norway, and Finland. I was able to find 2020 growth forecasts both before and after Covid-19 struck [1]. The following chart shows these estimates:

From this information, along with an estimate of Sweden’s 2019 GDP, we can calculate the loss in GDP Sweden prevented using their approach to managing the C19 epidemic.

First, we can determine the reduction in GDP growth for each country due to the C19 epidemic. This reduction is the difference between the pre- and post-C19 GDP growth estimates. Visually, that’s the length of the bars in the chart above. Sweden’s 2020 GDP was forecast to grow by 0.2% prior to C19 hitting; after the pandemic began, that estimate was revised steeply downward, to -4.8%. The net effect of the pandemic on Sweden? A 5% drop (from +0.2% to -4.8%) in GDP growth.

Interestingly (but not surprisingly), the net effect of the C19 pandemic on the GDP growth for the other Nordic countries is forecast to be greater than that for Sweden: a 5.8% drop for Denmark, 7.9% for Norway, and 6.4% for Finland. The simple arithmetic average reduction for these countries is 6.7%.

Now we’re getting somewhere. The difference between the reduction in GDP that Sweden is facing (5.0%) and that for its comparator countries (6.7%) is a proxy for the hit in GDP growth that Sweden avoided by foregoing more stringent lockdown strategies. In other words, based on the effect of C19 on the other Nordic countries, we can estimate that had Sweden implemented a lockdown approach, its 2020 GDP would contract by 6.7% instead of by the estimated 5.0%.

What is that worth in dollars? Well, the 2019 GDP for Sweden was estimated to be $564.8 billion in purchasing power parity [2]. Our estimate is that Sweden avoided an additional 1.7% drop in GDP due to foregoing a stricter approach to managing the spread of the virus — a savings of approximately $10 billion ($564.8 billion x 1.7%).

So… Is the Swedish Approach Working?

It’s not possible to say whether the Swedish strategy is succeeding because it depends completely on what one means by “working.” If the above estimates are roughly correct, the Swedish approach is failing from a public health perspective; as of 20 May 2020, an additional 3,700 deaths can be attributed to the approach.

On the other hand, if by “working” we mean reducing harm to the economy, the answer could be in the affirmative. Based on comparisons to the forecast effect of C19 on the other Nordic countries, Sweden has prevented an economic loss of about $10 billion.

We can combine these two effects of the Swedish approach — one positive, one negative — to gain some insight into the tradeoff that Swedish policymakers are implicitly making by pursuing this strategy. Specifically, we can calculate how much money Sweden has avoided losing per extra C19 death they’ve accepted. That’s simply the GDP loss prevented ($10 billion) divided by the excess number of deaths (3,700): about $2.7 million per life lost.

In other words, the Swedish approach (based on this admittedly back-of-the-envelope analysis) implicitly asserts that the value of an additional life saved (by reducing C19 deaths) is less than about $3 million. Interestingly, the threshold value recommended by Swedish authorities for policymaking is reported to be 2.4 million euros… just slightly less than our estimate and therefore consistent with the approach they’re taking to the C19 epidemic [3].

Some Additional Considerations

Lots of Caveats

First, note that our estimate of economic harm avoided is based solely on differences in projected GDP growth rates before and after accounting for C19. These are only estimates, and it’s possible that the world-wide effects of C19 will swamp any financial savings Sweden hoped to gain. It’s also possible that the forecasts were too negative for Sweden, in which case the savings they achieve could be greater than we estimated here.

Second, we only looked at differences in C19 deaths per 1M population to date (20 May 2020). If no vaccine is identified and no breakthrough treatment is discovered before herd immunity is achieved, it’s likely that C19 deaths in other countries will roughly”catch up” with those of Sweden. If that is the case, the lockdowns in those other countries may bear a financial cost for the sake of delaying only somewhat deaths from C19. On the other hand, at least in the near term, it’s probably reasonable to expect the C19 deaths per 1M population in Sweden relative to its Nordic neighbors will grow. That means that the $10 billion in savings will be spread across more deaths, lowering the implied value per life.

Finally, this is a simple, back-of-the-envelope analysis ignores all of the secondary effects. Specifically, lockdowns may impose negative (as well as positive) health and social effects in addition to reducing transmission of the C19 virus. Similarly, a stronger economy may cause other effects not well captured solely in monetary measures. These impacts are ignored in this analysis.

The Tradeoff Between Money and Life

Having to think about how much society should be willing to pay to reduce risks to the health of the public is not unique to the management of an epidemic. Transportation, environmental, workplace, construction, food, medicine and healthcare regulations must all determine what level of risk is acceptable. If they set that acceptable risk too low, everything becomes much more expensive… too expensive for many. If they set it too high, the population begins to suffer while not enjoying adequate economic offsets.

We should also note that as individuals we make similar decisions. In general, we accept some risks to life in order to enjoy other benefits. We are willing to drive our cars to go out to dinner (if that’s allowed!) even though there’s a chance that we’ll die in a traffic accident as a result. People engaged in more dangerous jobs are generally paid more — our way of compensating them for the excess risk they take on to work in mines, fight fires, or arrest bad guys.

The Value of Life in the United States

In the US, the value of a statistical life is thought to be about $10 million, at least according to recent research [4]. And that’s consistent with values imputed from decisions made by the Department of Transportation, the Environmental Protection Agency and the FDA [5]. Putting a value on a statistical life may seem unethical or unappealing, but it’s a necessity for policymakers to do their jobs. When regulators make decisions about the margin of safety needed in constructing bridges, for example, they cannot assign an infinite value to a statistical life. If they did, bridges would be infinitely expensive. The same argument holds about food, airplanes, medications… pretty much any technology that carries with it a potential risk to human life.

Notably, the value of a statistical life in the US is far higher than that in Sweden. This means that a strategy that makes sense in one country might not make sense in another… even if the outcomes were exactly identical.

What Does this All Mean?

Policymakers around the world continue to decide how to battle the spread of the C19 virus. We currently lack an effective vaccine, there is not a breakthrough treatment for those who get sick from their infection, and most countries don’t have enough tests and contact tracers to corral the virus. That means that we are left with a choice about how much to limit interactions with other people, which can be hard on the economy.

Sweden has taken one of the most relaxed approaches to managing the spread of the C19 virus. Based on this simple analysis, the Swedish decision implies a value of life of something less than about $3 million. In the US, this would be far too low a value for most policymakers; our threshold is more like $10 million per life saved. But the threshold in Sweden is lower, and is in line with the value that this simple analysis suggests.

In short, whether you view Sweden’s approach as brilliant or foolish depends to some degree on whether you embrace or reject the value that they place on a life. That value may seem too low (it does to me), but it is consistent with a value that they were using before the C19 virus came along. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised by the approach they’re taking.

Sources

[1] Estimates of Sweden’s GDP growth before and after accounting for the effect of C19 can be found here. Similar estimates for Denmark and Norway can be found here and here, respectively. An estimate of Finland’s GDP growth before accounting for the effect of C19 can be found here; an estimate after accounting for the effect of C19 can be found here.

[2] For an estimate of the 2019 GDP of Sweden, check this out.

[3] At least according to Wikipedia.

[4] See “The Value of a Statistical Life” by Keisner and Viscusi.

[5] Again, according to Wikipedia.